A high shrill scream distantly sounds from high in the sky. I scan the endless blue for the source of the noise. Sure enough, against the sun there is a jet-black anchor-shaped bird arcing left and right, spinning and banking, dipping and swooping. It moves jerkily, but unfazed by the strong wind. As it moves a silvery sheen glazes its feathers, giving an impression like a silky trail of oil. What places has it been, what journeys has it made? There is no knowing the life it has had. But one thing is certain: it has come a very, very long way to be back in our May skies.

Swifts are amazing record-breaking birds which spend most of their lives in the air. They eat, drink and even sleep on the wing, hanging on the convection currents, or thermals, for support. On top of that, they make a huge migration to South Africa and back to the UK every year. They strike me with awe every time I see one, and I ponder the journey it has made to get to me, streaming through the clouds.

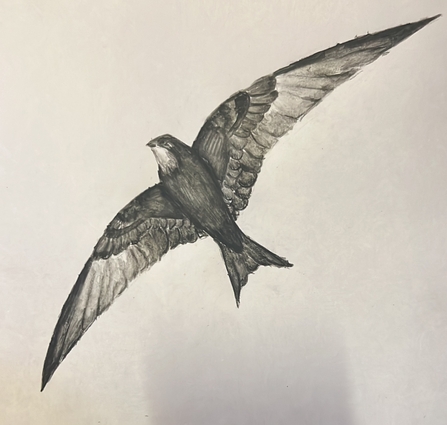

They're amazing! Everything about their bodies are designed for sustained flight. Their streamlined ‘falconoid’ shape and slender wings are perfect for speeding through the city streets where they spend much of their time. Their all-black bodies and scythe-shape make this species almost unmistakable; the swallow family of similar size and shape all have paler areas on their belly or rump. The only white area on a swift is it’s large throat patch, but this is rarely visible and swifts are, as the name suggests, very fast and so these details can be hard to pick out. At top speed swifts reach 69 mph!

A swift drawing (credit: Oscar Lawrence)

The common swift, apus apus, is the UK breed and is common across most of Europe but alpine swifts can also be seen as overshoot migrants on the coast of Norfolk in spring. Alpine swifts have a white belly and throat, they are much larger and are browner on their back and wings. Many overshoot migrants occur because of high pressure systems in normal breeding grounds; they fly north in search of more temperate climes, and reach Britain. Small numbers mean breeding of such species is very irregular, because two birds encountering each other becomes very unlikely. The common swift, is the main swift you’ll see here!

Common swifts arrive usually in the first week of May and nest in cracks in the brickwork of houses in suburbs and isolated villages. They have adapted from using ancient breeding grounds on sea cliffs and pine trees to now human-created habitats, taking advantage of holes or missing bricks in houses.

Unfortunately, in modern homes there are little to no gaps in brickwork or cracks under eaves which leaves no room for our swifts to nest, but there are several ways we can help them. Many people are now putting up swift boxes, and hollow swift bricks are now a requirement for newly built homes. This is a huge step in the right direction, giving this species a leg (or wing) up for conservation success.

All in all, swifts put the magic in summer, and to see them yet again screaming through our skies is a great joy. They never tire, never rest. They migrate thousands of miles every year. They really are nothing short of unbelievable.